Yesterday was a black Monday for Swiss private banking as one of the oldest institutes went bust. However, the writing had been on the wall: the demise of Bank Hottinger to a certain degree was predictable.

The origins of Bank Hottinger & Cie reach back to the year 1786. The Hottinger merchant dynasty, who had emigrated from Zurich to Paris, opened their first institute on the shores of the river Seine, and contributed ever since to the good name of Swiss private banking.

Tradition and longevity don't help much when the going gets tough. After 229 years of existence, the bank yesterday was forced to throw in the towel: Swiss banking regulator Finma opened bankruptcy proceedings against the bank as finews.ch reported. The house faces «overindebtedness» resulting from the costs of the liquidation, the regulator said. The bank's website disappeared on Monday evening.

Talk of the Industry

The demise of Hottinger was talk of the day in the industry and will remain so for a while. Rival institutes will have taken notice of the fact that Hottinger couldn't even be sold to a competitor anymore.

Hottinger wasn't the only private bank fighting for its life. Consultant KPMG considers a third of the industry to fall under this category. The authors of the KPMG study said that 28 percent of private banks had posted a loss in 2014.

«Hottinger Effect»

The «Hottinger effect» may become a buzzword in an industry undergoing a restructuring and consolidation process. «You can't exclude that primarily smaller private banks will meet the same destiny,» a reputed banking expert told finews.ch on condition of anonymity.

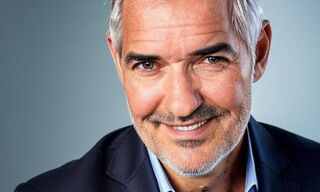

«The crash is exemplary for institutes who have done too little to develop a profit potential with a future, because they are busy cleaning up their black money past,» said Bernhard Koye, professor at the Kalaidos University of Applied Science in Zurich.

The problems that toppled Hottinger may have been home made, but are familiar in the industry:

-

Missing Structural Change

Hottinger profited from banking secrecy for decades, like everybody else. The new paradigm of «white money» hit the Zurich-based bank hard. The Hottinger family tried in vain to change course.

The clean up required following the moving of the goalposts brought about an existential crisis for the bank. Family and management of the bank in the summer of 2014 injected 12 million francs of new money, as finews.ch reported.

This was intended to cover for the looming fine in the U.S. To resolve the tax dispute with the tax authorities in the U.S., the bank had to make provisions of 4 million francs, admitting indirectly to have managed untaxed money with a link to the U.S.

Finma didn't say how much money the bank has today. The fact that no buyer could be found for an institute with such a heritage serves as an indication that the bank probably had too few assets with a clean background. Sources expect the figure to be closer to 1 billion than to 10 billion francs.

-

Unclear Strategy

«Sustained losses and unresolved litigation» led to a situation, where the bank no longer met the minimum capital requirement, Finma said yesterday. The effort to restructure the business wasn't successful – in other words, a reorientation in the era of «white money» couldn't be achieved.

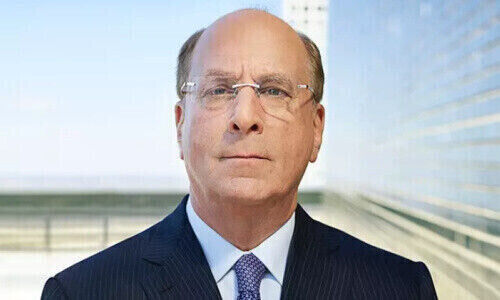

The bank did try however. In 2010, the institute changed from being partner owned to a shareholding. At the time it had eight branches in Switzerland and a further 13 in eight different countries. Frédéric Hottinger was chairman, Paul de Pourtalès chief executive.

The change of its structure was the basis for a further growth strategy, the bank hoped.

But as soon as 2012, Hottinger said goodbye to its growth plans and started negotiating with Banque Cramer about a cooperation. Why the talks failed isn't known, but the expansion of the business with independent wealth managers (see point 3) in Geneva caused a stir. In brief: Hottinger continued on its own.

Instead of growing, the bank shrunk its business. In 2012, Hottinger cut jobs (finews.ch reported). By 2015, the bank had some 150 employees in Zurich, Geneva, Brig, Sion, Basel and New York.

The management of the bank underwent change as well: Jörg Auf der Mauer, who had replaced de Pourtalès in 2011, joined consultant BDO in January. André Reichlin stepped in for him. Jean Roch had taken the chairmanship at the end of 2013. People close to the bank said the management had been restrained by disputes among the owners of the institute.

An answer regarding this question from the bank wasn't immediately available.

With the injection of fresh money in 2014, the strategies had given way to a fight for survival. The failure serves as a warning that Swiss private banking, once a lucrative industry, has become much tougher and competitors needs to leap at the opportunities available.

-

Destroying Your Reputation

Bank Hottinger didn't just fight for survival, but also for its reputation. It wasn't only the tax dispute with the U.S.: Hottinger et Partners, the Geneva-based asset manager, in 2013 was engulfed by news about a case of fraud. According to reports (see finews.ch), a substantial sum of customer assets were defrauded.

Hottinger et Partners were separate from Bank Hottinger, but Frédéric and Rodolphe Hottinger founded the asset manager and the damage to the reputation will also have affected the Zurich-based bank.

-

Too Little to Survive

Most private banks manage less than 10 billion francs – and continue to exist. It is thus difficult to say how much a bank needs to retain sustainable profitability. Smaller banks do however have a problem with costs. A small bank tends to spend more money to manage every billion than their bigger competitors. Hottinger, with – at the end – some 50 employees and 1,500 clients may have been too small.

-

Digitalization

Bank Hottinger did without the Avaloq and Finnova standard IT platforms, according to media reports. The frequent strategic changes will have been challenging for the IT department and a strain in respect to the adaptation of new technologies.

Industry experts frequently say that the digital world allows private banks to develop their niche. The case of Hottinger however suggests that a bank fighting for survival won't find the breathing space to develop meaningful fintech projects.