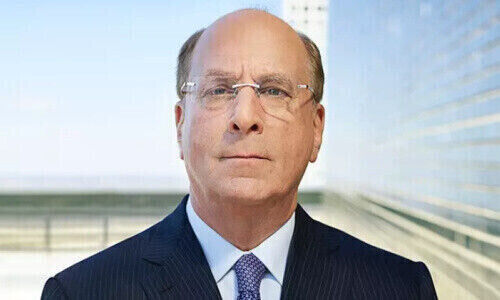

Georges Blum, former chief executive and president of Swiss Bank Corporation, has written a fascinating book about the creation of the modern day UBS, trying to make sense of the merger. Particularly poignant is the part devoted to Marcel Ospel.

By Robert U. Vogler, historian and former UBS spokesman*

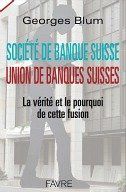

The book is written in French, which in part explains why the book hasn't yet been highlighted in the German-speaking media of Switzerland. It contains a number of interesting explanations and a narrative of the events leading to the merger between Swiss Bank Corporation and the old UBS in 1998.

There's no escaping the fact that there has been discord in the build up and the implementation of the biggest merger in the history of Swiss business, not least at SBC.

Ospel's Fierce Attack

The following story gives an impression of how the merger at SBC took shape. In November 1994, Marcel Ospel, then head of international business at SBC, invited his boss and CEO, Georges Blum, to a meeting outside the bank's offices. During the meeting, he leveled fierce accusations at Blum.

Ospel said he had lost authority in the eyes of a large portion of his management because Blum had displayed his doubts about Ospel's interest in the unit he was guiding. There were two solutions to the problem, Ospel went on: Either Ospel would be asked to leave the bank or Blum would surrender the job of CEO to him.

Management Buy-Out With Martin Ebner

Blum writes that this was an obvious attempt by Ospel to make undone the decision to appoint Blum and not Ospel as CEO in 1992. The latter also threatened with a management buy-out assisted by Martin Ebner's BZ Bank and a group of investors.

It proved a non-starter even though Ospel went on to present Walter Frehner, the chairman, with equally far-reaching demands for a reconstruction of SBC. Blum concludes in his book that the redimensioning of the bank planned by Ospel and his faithful aimed at enabling the personal enrichment thanks to a weaker risk control with fewer managers and names this an «adventure». For today's reader with vivid memories of the UBS debacle, this reads as a prophecy.

Clandestine Meeting

At the first meeting in clandestine circumstances with UBS, represented by chairman Nikolaus Senn and CEO Robert Studer in April 1995, Blum sensed a certain interest from their side but also the firm opinion that there's was the stronger position with a corresponding ambition to take the lead.

In a late telephone call, Studer suggested to Blum that he (Studer) should become chairman and Mathis Cabiallavetta chief executive officer of the new bank – a proposal that was completely unacceptable to Blum. To him only the splitting up the two top positions between the two banks would do.

UBS – Inert Giant

The inert giant, which still had the financial firepower, flexed its muscles. Later, this would be upset when SBC managers assumed the managerial responsibility. The merger of equals envisaged by Blum never really took place.

UBS' interest cooled subsequently as personal interests took precedence. The bank also had to deal with BZ Bank and Martin Ebner. In April 1996, Studer took over as chairman and Cabiallavetta was named CEO, almost simultaneously as Blum moved up to chair SBC, with Ospel as his CEO.

Tricked Into Takeover

At a meeting in New York, Studer accused SBC to harbor hopes to trick UBS and assume control over the rival institute. After the blunt refusal by UBS to merge with Credit Suisse, SBC had renewed hopes for a merger.

Meanwhile, Ospel had started reconstructing SBC and Blum got concerned about the pronounced ego of the CEO. According to Blum, the two would be able to complement each other well, but Ospel had a tendency to criticize all and everything.

After many internal discussions the two banks moved closer again and Ospel was in charge of the talks for SBC. The solution preferred by the participants foresaw a co-chairmanship of Studer and Blum, with Cabiallavetta as CEO and Ospel as head of international business, ie investment banking. Shortly after the two sides came to the conclusion that the conditions weren't advantageous and stopped the new attempt.

Both Could Have Survived

But then, the decisive moment came. Ospel had constructed such a strong position within the management of SBC that another rejection of a merger attempt by the board would have led to a mass exodus among the executive board.

Ospel proceeded to threaten with his resignation and the board relented, accepting a merger. This paved the way because pressure at UBS had mounted following massive losses in Japan, prompting Cabiallavetta to move close to Ospel on October 16, 1997.

Blum concludes that neither bank really needed the merger and would have been able to survive independently. However, SBC was in a less comfortable situation because its capital base had thinned following a string of overpriced acquisitions.

UBS was much stronger in terms of capital and also healthier than SBC, even in the light of the losses incurred through the LTCM hedge fund, which led to the downfall of Cabiallavetta and to the ascension of power of the old SBC management.

Blum is saddened by the fact that nothing much is left of the old SBC, with the new bank carrying the same name in French and English as the old merger partner. He also repeats a dictum by Nikolaus Senn at their first meeting in 1995, that one and one never makes two. How right he was.

Blum is saddened by the fact that nothing much is left of the old SBC, with the new bank carrying the same name in French and English as the old merger partner. He also repeats a dictum by Nikolaus Senn at their first meeting in 1995, that one and one never makes two. How right he was.

Georges Blum, Société de Banque Suisse – Union de Banques Suisses, La Vérité et le pourquoi de cette fusion, Editions Favre, Lausanne, 2015.

Robert U. Vogler is a historian and spokesman of UBS from 1988 through 1998. Later, he was head of historical research and senior political analyst at UBS Public Policy. Today he works as an independent historian.

Robert U. Vogler is a historian and spokesman of UBS from 1988 through 1998. Later, he was head of historical research and senior political analyst at UBS Public Policy. Today he works as an independent historian.