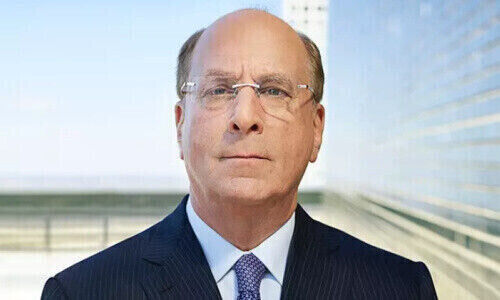

An abysmal fourth quarter, lingering concerns over capital adequacy, and a near-reversal of strategy have cast a shadow over Credit Suisse's board. Considerable criticism has centered around CEO Tidjane Thiam, who has been running the bank for just over six months.

How much support Tidjane Thiam manages to garner internally will play a decisive role in how effectively strategic changes and cost cuts are implemented in coming months.

But what role does Credit Suisse’s board of 12 directors play in the bank’s current situation? Though one board member – Seraina Maag – has less than one year’s experience on Credit Suisse’s board, the average tenure of the remaining ten members under chairman Urs Rohner is nearly 6 and a half years, raising questions over their culpability for the bank’s current dilemma.

Here’s a look at some of the problems facing Credit Suisse’s board:

1. Long Lead for Dougan

The board granted former chief executive Brady Dougan, who by his own account lived and breathed Credit Suisse during his 25 years with the bank, an unprecedented free hand in setting and implementing strategy when he became CEO in 2007.

This worked well during the financial crisis, which Dougan is widely credited with making the type of savvy quick-fire decisions which navigated the bank through without a state bailout, unlike crosstown rival UBS.

The board’s hands-off approach was less successful in later years, when Dougan held on to Credit Suisse’s expansive and costly investment banking setup for too long. He also left the bank at a severely depleted level of capital, forcing it to scramble to raise funds shortly after he departed.

2. Thiam’s Carte Blanche

The initial months of Thiam’s tenure as CEO confirm that the board isn’t carrying its weight on setting a strategic direction for the bank. Credit Suisse’s new strategy, which effectively reverses its former «one-bank» approach, bears the imprint of Thiam, who took over from Dougan in July of last year.

Thiam and what Credit Suisse insiders refer to as an army of influential consultants have been granted carte blanche over the bank’s new strategy, and have left practically no stone unturned.

3. Few Bankers on Credit Suisse Board

Credit Suisse’s board has few representatives with bottom-up banking experience: Kai Nargolwala and Dick Thornburgh – both former Credit Suisse bankers – come closest, but they have struggled to assert their influence.

Noreen Doyle spent 13 years with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, or EBRD. Qatar’s representative, 33-year-old Jassim Bin Hamad J.J. Al Thani, has spent his career in finance and private equity. He has done little to disperse the impression that he is merely Qatar’s proconsul at Credit Suisse.

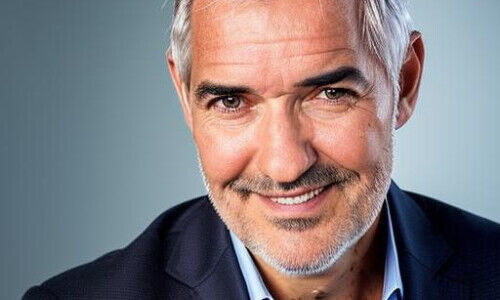

Chairman Urs Rohner, a securities lawyer who spent time in the entertainment industry, has always carried the stigma that he hasn’t spent enough time as a banker to lead a bank himself.

Long the bank’s lawyer and operating chief before moving to the board, Rohner’s s appointment as chairman was reportedly delayed by one year at the behest of Switzerland’s regulator, Finma, which objected to Rohner’s lack of banking experience.

4. A Board With Talent

Credit Suisse’s board is an enviable laundry list of talent and experience. Sebastian Thrun helped build Google’s driverless car; Iris Bohnet is a tenured professor at the Harvard Kennedy School in Cambridge, Mass.; Severin Schwan runs pharmaceutical giant Roche; John Tiner headed Britain’s regulator, the Financial Services Authority, for four years. Regrettably, the board’s accumulated knowledge and experience is virtually imperceptible when it comes to the bank.

5. Qatar’s Influence

With a stake of approximately 5 percent in Credit Suisse and purchasing rights for another 13.6 percent, Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund is the bank’s weightiest investor. Accordingly, it has had an influential voice on setting Credit Suisse’s strategy.

Though the fund is extremely secretive about its investments, it clearly backed Credit Suisse’s former strategy of betting on investment banking even after Swiss regulators imposed some of the world’s strictest capital rules on riskier business, sharply hiking the cost of business. Qatar’s influence on Credit Suisse’s strategy may not be visible at first glance, but it is substantial.

6. Chairman’s Role

Credit Suisse has been traditionally a thought leader when it comes to economic and political questions facing Switzerland, a role it purportedly wants to maintain. Urs Rohner’s contribution to this has been modest to date, barring an interest in fintech and new entrants to banking.

Because Credit Suisse’s last two CEOs have been foreigners, it falls to Rohner alone to address politico-economic or sociopolitical debate in Switzerland. With issues such as a record-high Swiss franc, uncertainty over immigration and labor and the broader question of Switzerland’s attractiveness for business at stake, Rohner is conspicuous by his absence.

7. Who Asked for a Dividend?

Credit Suisse’s decision to pay a dividend of 0.70 Swiss francs per share – the same as the two previous years – is mystifying given the bank’s precarious capital position. Presumably, weighty investors insisted on receiving a payout.

Investors can cheer Credit Suisse as one of the best dividend-yielding banking stocks, but the decision to pay a sizeable dividend given the bank’s ill health, poor results, and uncertain outlook is questionable.

8. Board’s Last Call

Thiam is overseeing a major overhaul of Credit Suisse that he says will take 2 to 3 years to judge the success of. For now, the vigor of his actions are sure to win him powerful enemies within the politically charged ranks of Credit Suisse.

That means the board is under pressure to show strong backing for Thiam’s plans to split up the bank into regions and offload a minority stake in its lucrative Swiss bank unit. Otherwise, the board risks undermining Thiam’s efforts before they have begun.