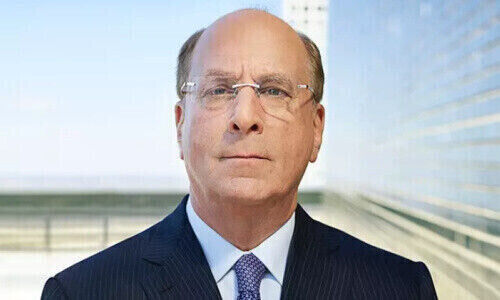

Jason Chandler oversees more than $1.2 trillion of UBS’ assets and nearly 6,500 private bankers. The former collegiate soccer player is the linchpin to the Swiss bank's efforts to make a super-rich push truly global.

The American-born banker has been head of UBS’ wealth management activities for 17 months – and central to the Swiss bank’s efforts to truly span the world for the ultra-rich. A soccer scholarship got him to college, but Jason Chandler switched to business when it became clear his coursework would interfere with practice.

The U.S. unit is attempting to duplicate what UBS does in Asia, Latin America, or Switzerland: be and do everything to and for wealthy clans who command enough volume to merit the attention of investment bankers. Locking in this client segment globally, including the U.S., would lend credence to UBS’ sudden mega-merger in 2018.

«Can't Be Amazoned»

UBS’ plan is underpinned by sheer volume: the Americas are still home the most billionaires. The U.S. has four times as many super-rich – those with more than $50 million – than China in second place, according to a recent Credit Suisse study. It falls to Chandler, the father of three teenage girls, to prove that it can adopt an advice-based, European-influenced model among its fee-driven brokers.

«The wealth management business is durable, I don’t think it can be Amazon-ed, Uber-ed, or AirBnB-ed,» the 49-year-old said last year. «It’s a relationship business where advice is specific to the family and to the client.» Personable and charismatic in the style of Americas Chairman Robert «Bob» McCann, Chandler faces major changes at the U.S. unit in the midst of a pandemic and as a severe recession looms.

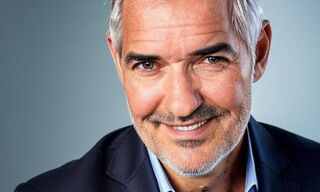

Like his boss, Tom Naratil (pictured below), Chandler got his start as a trainee at Paine Webber. He never left, though Chandler leapfrogged the man who hired him, John Decker, more than ten years ago (Decker still works for UBS as New York market head).

His most pressing challenge is profitability in a tough, expensive year: UBS, where productivity averages $1.3 million per adviser, wanted to move the goalposts for its advisers, making it tougher for them to reach payout targets. Chandler was forced to postpone the effort when the coronavirus hit the U.S., to autumn at the earliest.

Lagging Profitability

The U.S. unit’s profitability lags that of the wider unit, dramatically so (though it is improving): the Americas posted a cost-income ratio of 83.1 basis points in the first quarter, compared to 72.4 basis points in the wider unit (Switzerland, at 57.4 basis points, is a standout).

Chandler, who still plays soccer and has coached his daughters' teams, has spent the entirety of his career in the U.S. market but dipped into the wider world when he briefly co-ran an investment product and solutions group with Swiss banker Christian Wiesendanger.

Breaking Gridlock

The now-disbanded unit was one of the first to pool efforts worldwide to source products for ultra-wealthy clients, long before the 2018 merger.

A break in UBS’ gridlock has also helped him: the U.S. private bank won $9 billion in first-quarter inflows for separately-managed account strategies provided by its asset management unit, following price concessions, he told «Barron’s» last week.

The specifics of UBS' American push includes moving top investment banker Reinhardt Olsen to its private bank five months ago. More recently, the outline of a «one-bank» structure took shape recently under Paul Crisci, a veteran technology banker.

Lending Against Planes, Art

UBS' closest competitor – unless Credit Suisse revisits its 2015 decision to leave the U.S. wealth market – is Morgan Stanley. It is far more efficient than UBS (a 73-basis-point cost-income ratio in the first three months) and, like UBS, is quietly trying to tap Asia’s ultra-wealthy through partnerships.

UBS also started lending more aggressively in the U.S.: its loan book fattened by $5.5 billion in the last two years. At just north of five percent, its loan penetration with American clients is still relatively low. Chandler emphasized advice as much as lines of credits against luxury homes, planes, or pieces of fine art.

«Our wealthy clients are looking to be flexible: when they see something, to do something. When they want to buy something, to buy it,» he noted. «So having access to credit provides flexibility for our clients,» he told «Bloomberg».